In the fourth instalment of our series on the ‘History Around the Coast Path’, guest writer and SWCPA Chair, Bob Mark, explores the South West’s role in the making of Britain and the foundation of our parliamentary monarchy.

It has been estimated that by the time the British Civil Wars were over in 1660, at least half-a-million people had perished in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, from an estimated total population of five million. Greater than the proportion of British losses in any of our twentieth-century wars. One in ten. A decimation of epic proportions, which ripped families apart and tore at the very fabric of society. Yet no one saw this coming. James VI, King of Scotland, inherited the English throne peaceably from Elizabeth in 1603, as James I of England. James’ overriding ambition was to re-unite his two kingdoms as ‘Great Britain’. James even argued that the ‘Brutus Stone’ in Totnes was evidence of the legendary founder of an earlier, unified, British kingdom and so surely it was right to bring unity once more. Not a Scots Nationalist, James VI!

James’ obsession to establish himself as the divinely appointed monarch of a Great Britain was shared by his son Charles I. Religious practice was also to be ‘tidied-up’ through a new common prayer book and hierarchy of Bishops. England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland were indeed to be forged together as ‘Great Britain’ by 1649, but not under a monarchy. Great Britain came into being through Civil War as a republic, and the revolution which preceded this republic was the model for those which were to follow in America in 1776, and France in 1789. A little startling when we reflect that revolutions are not ‘foreign’, popular revolt started ‘over here’ not ‘over there’. Can we still see evidence of these upheavals around the Path? The answer is, if we look carefully, a very great deal.

Prelude to Civil War

It is a common misconception that the British 17th century Civil Wars were solely wars of religion. They were not. Religion played a huge part, but these wars were triggered for strikingly modern reasons. Here is Edmund Ludlow, sometime MP for Wiltshire, later a Parliamentary General, trying to make sense of the sacrifices of it all in his memoirs. In Ludlow’s view, these wars were fought to determine, ‘whether the king should govern as a god by his will and the nation be governed by beasts, or whether the people should be governed by themselves, by their own consent’. These issues were debated by a literate population, even in the remote south-west. We can still walk the same rooms, where Ludlow discussed these issues with his in-laws at 16thcentury Montacute House, now National Trust. A wonderful atmospheric house.

So what started the revolt? Money! James had called Parliament very rarely in his reign, steering clear of expensive foreign wars. Charles inherited his father’s deficit, he needed money, he waged war with Spain, and followed up with a disastrous war against France. When his first Parliament set conditions for new taxes, he determined a period of personal rule which was to last 11 years. During this time, Charles ruled as an autocratic, absolute monarch over the three nations, without recourse to a Parliament, and resurrected various old statutes to raise funds. Most notoriously he instituted a feudal levy known as ‘ship money’. Charles alienated a broad swath of his people, leading to widespread discontent, court cases, and even riots. One of Charles’s most bitter opponents during the period of personal rule was Sir John Elliot of St Germans in Cornwall, whose health was broken by imprisonment in the Tower. When Parliament was recalled, its leader became John Pym, a Somerset man. Two years after the ending of the period of personal rule, in 1642, the country slid into Civil War. The West Country was split. Cornwall was predominantly for the King. Devon, Somerset and Dorset predominantly for Parliament.

The War in the South-West – The Breaking of Family and Friendships

From 1642 to 1646, Civil War shattered the peace of the South-West, separating friends and even families into taking opposite sides. Royalist verses Parliamentarian. Consider the case of Sir Alexander Carew of the National Trust’s Anthony House. Anthony overlooks the river Lynher just as it meets the Tamar. A handsome house 4 miles north-east of the Path as the walker passes Tregantle Fort near the Cornwall/Devon border. If you visit the library in Anthony, your gaze may fall on curious, rough, over-painted stitching between top and bottom of the frame and an otherwise beautifully finished full-length portrait of Sir Alexander. Why so?

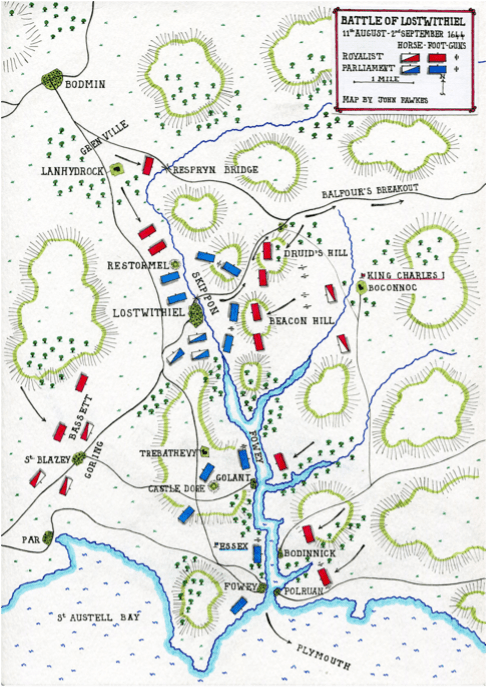

In 1642, Carew sided openly with Parliament, one of the few Cornish Gentry to do so, by March 1643 he was made governor of St Nicholas’ Island (now Drake’s Island), a key defensive position for Plymouth. A town staunchly for Parliament. However, the summer of 1644 was the high point of Royalist success in the southwest. In the battle of Lostwithiel, the Royalists shattered Parliament’s main army which, under the Earl of Essex had enjoyed success in relieving Lyme Regis and had followed the retreating Royalist forces into hostile Cornwall. Key to the victory at Lostwithiel was the Royalist decision to occupy the old fort at Polruan at the mouth of the river Fowey. Cannon mounted here prevented the Parliamentary Navy from landing supplies or evacuating troops from Fowey. Polruan’s ancient 14th century blockhouse, on the left of the picture below, dominates the entrance to Fowey Port. The Royalists occupied the East bank, and the Parliamentarians were trapped on the west bank, roughly occupying a 5-mile by 2-mile corridor from Lostwithiel to Fowey, pressured by Royalist armies on all landward sides, and cut off from hope of rescue by the Fleet.

The Earl of Essex ordered the two thousand men of the Parliamentary cavalry under the command of Sir William Balfour to break out and fight their way to the Parliamentary stronghold of Plymouth. Essex slipped away in a fishing boat to join him. However, there was no escape for the 8,000 Parliamentary infantry who retreating from Lostwithiel, made a valiant last stand at Castle Dor under Major General Philip Skippon. It is estimated that only a 1,000 survived to fight another day. The King was victorious.

What of Sir Alexander Carew and the mystery of his portrait. Carew’s decision to join the Parliamentarian’s had split the family. It is said that he was cut from his portrait in disgust. The King’s victory at Lostwithiel in September could not be ignored, Carew had just inherited his late father’s Anthony estate. He now faced potential ruin on the losing side. Carew was suspected by the Parliamentary commanders of the besieged Plymouth garrison of treason, he was relieved as the commander of St Nicholas’ Island in Plymouth Sound and sent to London for trial, execution followed in December 1644. The family promptly had him sewn back into his frame. Rehabilitated in the eyes of his Royalist relatives. Although his half-brother John was to remain true to Parliament’s cause, signing King Charles death warrant in 1649. The small museum at Anthony House tells the story of both brothers. Walking down lanes hardly changed, between Lostwithiel and Fowey, crossing as the coast path walker does to Polruan, it is hard to imagine that this peaceful landscape of low hills, hedges, and quiet meadows was the site of a month of fighting between 3 Royalist armies totalling around 18,000 men and 10,000 Parliamentarians, and that this area was the site of perhaps the King’s greatest triumph in the Civil War.

By 1646 the King’s fortunes had reversed and he surrendered himself to the Scots, who handed him over to Parliament. Parliament’s disciplined, professional, New Model Army under the inspired leadership of Sir Thomas Fairfax, with Oliver Cromwell as his cavalry general, had swept westwards capturing Royalist strongholds, bent on the relief of Plymouth which, under the resolute leadership of Lord Robartes of Lanhydrock, had endured two years of siege as the remaining Parliamentary stronghold in the SW. After success at Lostwithiel, the Royalist’s had hoped that their capture of the heights of Mount Batten, on the Path, just south of Sutton Harbour and the Cattewater, would make Plymouth’s re-supply by Parliament’s fleet impossible, but the Parliamentarians simply moved their critical logistics to Millbay Cove out of cannon range.

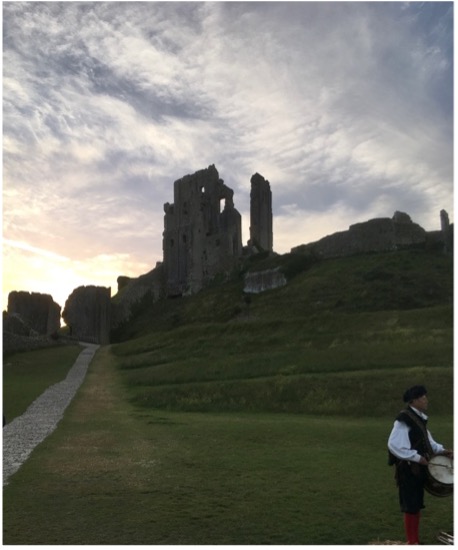

The positions were reversed further east in Dorset, which as early as 1643, was largely under Parliament’s control, with the exception of Corfe Castle, which was a stronghold held for the King by Lady Majorie Bankes. Lady Bankes endured two sieges in the castle, virtually impregnable, it fell by subterfuge in 1645. Royalist reinforcements brought into the castle were Parliamentary soldiers in disguise. The castle fell, and the people of the staunchly Parliamentarian town of Poole petitioned for Lady Bankes to be fined and the castle slighted. The monies raised to go to the relief of Parliament’s soldiers and the suffering townsfolk. Hence the romantic ruin of the castle today. Lady Bankes statue and the keys of the castle are proudly displayed by her descendants, restored to their fortunes by Charles II, at their new house of Kingston Lacy (NT). The last Royalist stronghold to fall to Fairfax was Pendennis Castle, held for the King by ‘Jack for the King’, Sir John Arundell of Trerice. The castle had been the last refuge of the heir to the throne, Prince Charles. With the war lost in the West, Prince Charles left Pendennis for the Isles of Scilly and from there to the safety of staunchly Royalist Jersey. After a five-month siege, the 1,000 or so Royalist troops had been reduced to eating their horses and were given honourable terms of surrender. Arundell’s eldest son was killed in the siege of Plymouth, his second son was to work in the Royalist secret society ‘the Sealed Knot’ during the Republic for the restoration of Charles II. Today Pendennis is in the care of English Heritage and Trerice, near Newquay is National Trust, both offer fascinating opportunities to walk in the footsteps of the Arundells.

Revolution & Restoration

By 1648, after a renewal of fighting instigated by the King, all hope of negotiating with King Charles I had been abandoned. Tried and condemned for making war against his people, Charles I was executed in 1649. Parliament declared England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales to be united in a Commonwealth, however the Act of Union bringing England and Scotland together did not come into force until 1651. The Scots Parliament had declared Charles II King of the Scots. Leading a largely Scottish army in 1651, Charles II was lured into England and defeated by Cromwell’s Commonwealth forces at the Battle of Worcester. He famously hid in an oak tree, before evading his pursuers and fled to Charmouth on the Jurassic Coast, disguised as an eloping lover. Charles narrowly escaped capture when the ship’s captain – Stephen Limbry – was locked in his bedroom and had his clothes hidden by his wife to stop him becoming involved in such a perilous undertaking! Charles finally escaped into exile from Shoreham. Cromwell ruled for 5-years as sovereign in all but name. Offered the throne, he declined, ruling as a constitutional ruler through a Council. When Cromwell died in 1658, after a period of chaos it was recognised that England needed a successor, not to Charles I, but to Oliver Cromwell. King Charles II was offered the English throne by Parliament in 1660, under certain conditions, promising indemnity to all but the regicides who had signed his father’s death warrant. John Carew, regicide, brother of Sir Alexander Carew, was tried and executed, adding to the tragedy of war suffered by the Carew family.

Charles II had a long memory of the people of Plymouth’s spirited opposition during the Civil War. It is for this reason that the massive Royal Citadel was built during the restoration years, both to defend Plymouth from attack and with cannon sited to overawe Plymouth. Throughout Charles II’s reign, the post of Governor of the Royal Citadel was the most important and highest-paid military governor in the kingdom.

Invasion and the ‘Glorious Revolution’

The Stuart restoration ended with the deposition in 1688 of his brother and successor, the Catholic James II, who had only reigned for 3 years. Now openly declared as a Catholic, James was at loggerheads with both his overwhelmingly Protestant Parliament, and his Church of England Bishops, seven of whom he sent to the Tower for insubordination, tried, and, to James’ fury, acquitted. James was also widely suspected of moves towards the absolute rule of his father, Charles I, by building up a Catholic-led standing army. The final trigger for what became known as the ‘Glorious Revolution’ was the birth of a Catholic male heir to the throne by James’ young Catholic Queen, Mary of Modena. This new Prince would disinherit both of Jame’s Protestant daughters, Mary and Anne from his first, marriage. Seven influential aristocrats invited William, Prince of Orange, Protestant hero and husband of James’ Protestant daughter Mary Stuart, to ‘rescue’ England. William was locked in a struggle with fanatically Catholic Louis XIV of France. War was coming between the William’s Dutch and his Allies against the expansionist ambitions of Louis XIV. The question was which side would England be on. England had recently fought wars against the Dutch, primarily over trade. Charles II had received secret subsidies from Louis XIV and James, if left on the throne, would surely side with France. William had to act. He seized the opportunity of the ‘invitation’. Assembling a huge invasion fleet, bigger than the Spanish Armada of 1588 and with 14,000 troops, evaded the English Fleet, and landed at Brixham in Devon. A statue of William stands on the Path on Brixham town quay.

William had little ambition to become King of England. He wanted to ensure the survival of the Netherlands against Europe’s superpower, France, and to lodge the British Isles firmly in the Alliance he was building against Louis XIV. William needed to come to terms with Parliament. The Bill of Rights of 1689, to this day is one of the crucial documents of English Constitutional Law. It establishes regular Parliaments, free elections, the right not to pay taxes levied without the approval of Parliament, outlaw’s cruel punishments and establishes Parliamentary privilege. It is interesting to reflect that in 2023, the very same Parliamentary privilege rules which led to the downfall of a former Prime Minister were defined by the need to find an accommodation between a Dutch Prince, William, and an English Parliament to determine if England would participate in a European struggle. That compromise would lead to 7 successive wars with France, until French ambitions were finally curtailed at the battle of Waterloo in 1815. Transform the West Country economy, lead to the birth of Devonport, Plymouth as the largest Naval Base in Europe and, as importantly, for this audience, the first establishment of a South-West Coast Path. The story for next time.

Written by Bob Mark

Chair, South West Coast Path Association

This article is the fourth in a series exploring the history around the landscape of the South West Coast Path. Read the other articles in the series:

History Around the SW Coast Path – Part I – Prehistory – The Age of Megaliths, Bronze and Iron

History around the SW Coast Path – Part II – Medieval

History Around the Coast Path – Part III – Late Medieval and Renaissance

Discover a selection of Heritage Walks on our website and explore the past as you travel.