The Victorian age brought tremendous change. Steam technology drove an engineering revolution, a mining boom to sustain it, massive inward immigration, and new prosperity in the south west. Today’s mainline railway network, with its navvy-muscle built tunnels, cuttings, viaducts, and bridges, remains as a magnificent achievement of the 19th century. The Duke of Wellington muttered darkly that these new railways would allow the working classes to ‘move about’ and so they did. Railways stimulated industry, expanded horizons, and brought visitors flocking-in, leading to the development of new holiday resorts like Lynton and Lynmouth, christened ‘little Switzerland’, and the expansion of the ‘English Riviera’ – around Torbay. On the north coast, paddle steamer services connected the great new industrial centres of South Wales with resorts such as Ilfracombe and Minehead.

The Railway Revolution – Mass Tourism hits the South West

Reaching the West Country had been slow, expensive, and difficult for the casual tourist. All that was about to change from the 1840s. Steam technology, pioneered in West Country mines, was on the move. The great age of Railway building had begun. From George and Robert Stephenson’s opening of the Liverpool-Manchester railway in 1830 with the World’s fastest engine, the Rocket. Nothing would be the same again. A horse and carriage could manage a steady pace of around 8 mph and require the horses changed after 10 miles or so. The Rocket could reach 30mph, 15 mph up an incline hauling a carriage of 20 persons. Carrying enough coal for a consistent 10mph over 70 miles.

The railways changed not just travel, but time itself, timetables required a standardised national time. By 1841, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, with the muscle power of thousands of navvies, had built the immensely difficult 118-mile line from London to Bristol for the Great Western Railway (GWR). It took another pioneering genius in 1844, JMW Turner, to capture and communicate that excitement forever in paint.

It’s worth a trip to the National Gallery to gaze on Turner’s ‘Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway’. Impressionism began with Turner. In 1844, GWR in alliance with the Bristol and Exeter Company brought the railways to Exeter. In the same year, Prime Minister Gladstone passed an act requiring the railway companies to offer 3rd class, cheap, tickets. Carriages were initially utilitarian, but everyone wanted to taste the new thrill of speed. By 1850, God’s Wonderful Railway – aka the GWR – was carrying over 2 million passengers a year. By 1875 – 36 million.

Image: Rain, Steam, and Speed, the GWR – Nat Gallery

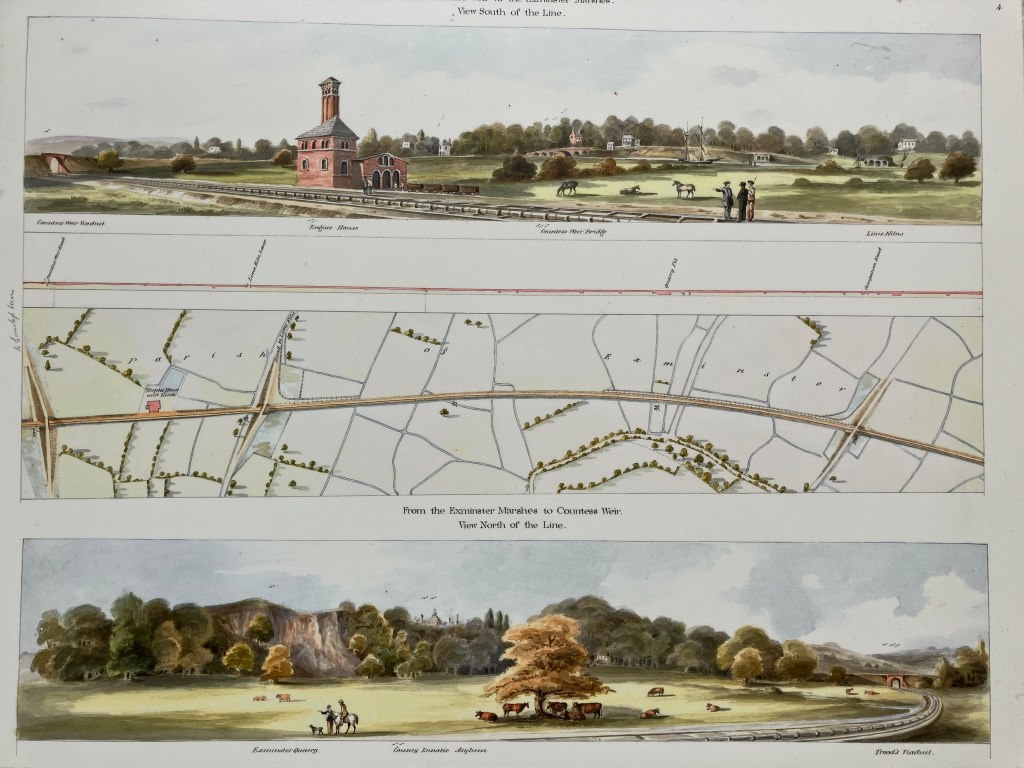

The far south west was still isolated. Brunel had surveyed a route to Plymouth, but the steep inclines of the southern fringes of Dartmoor were thought beyond the capacity of the steam locomotives of the day, so Brunel hit on an ingenious solution, ‘the atmospheric railway’ – no locomotives, passive carriages attached to a piston, driven along in miles of continuous 15-inch diameter pipe, with elegant ’Italianate’ pumping stations every 3 miles. The pumping stations created a vacuum in the cylinder ahead of the piston, which fitted through a slot in the pipe beside the track, as the train moved forward a greased leather flap opened, and then closed, behind the piston.

In 1847, a regular service of four ‘atmospheric’ trains a day, each way, began to operate between Exeter and Teignmouth. In 1848, the service reached Newton Abbot. The highest speed recorded was an average of 64mph with a 28-ton load, dropping to 35mph with a 100-ton load. Unfortunately, the idea was beyond the technology of the times. It proved impossible to maintain an air-tight seal, resulting in all the steam pumps working uneconomically to maintain the pressure differential. Aside from his engineering genius, Brunel was above all a realist, he recommended to the company directors that they abandon the scheme and revert to the rapidly improving steam locomotives. Today, the walker can see the best-preserved pumping station at Starcross. Brunel bought land in 1847 at Watcombe, Torquay where he extensively landscaped, planted, and intended to build a grand family home. A short detour from the path above Watcombe Beach allows a visit to Brunel Woods, to see the 50 ft, intricately carved, wooden monument celebrating Brunel’s achievements. The excellent volunteer-run South Devon Railway Association Museum has much more to tell.

The greatest single monument to Brunel in the West is undoubtedly the Royal Albert Bridge, opened in 1859. Brunel’s design of two 455-foot oval iron spans, each weighing 1,000 tons, suspends the single track 80 feet above the river. It’s estimated that in the past 160+ years the bridge has carried almost a billion tonnes of rail traffic.

Image: Royal Albert Bridge – Wikimedia Commons

Around 20,000 people came to see the floating out and jacking-up, under Brunel’s supervision, of the first span in 1857. It was a triumph and fitted perfectly. In May 1859, Prince Albert opened the bridge to huge rejoicing. This ballad written at the time captures the mood.

From Saltash to St Germans, Liskeard, and St Austell

Prince Albert

The County of Cornwall was all of a bustle,

Price Albert is coming the people did say,

To open the Bridge and the Cornish Railway.

From Redruth, and Cambourne, St Just in the West,

The people did flock all dressed in their best.

From all parts of England, you’ll now have a chance,

To travel by steam right down to Penzance

Sadly, no flags flew, no bands played, no crowds cheered when Brunel lay on a specially prepared platform truck, drawn beneath the spans of his new bridge by one of his friend Daniel Gooch’s locomotives for a last look at his masterpiece. Brunel was dying, his last enterprise, the immense trans-Atlantic liner, the ‘Great Eastern’, twice the length and ten times the displacement of Brunel’s earlier iron masterpiece the SS Great Britain, (now restored in her dock in Bristol), had broken his health. The SS Great Britain had been in 1843 the world’s largest, longest, and first iron-hulled, screw-propelled ship. The SS Great Eastern, more ambitious still, near bankrupted Brunel.

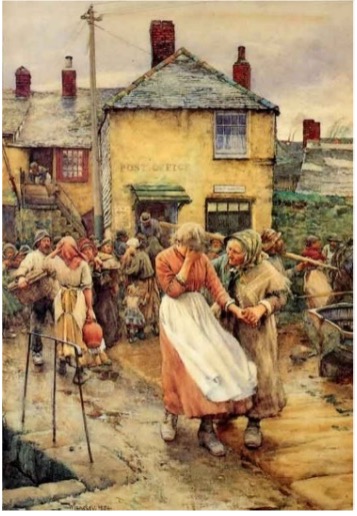

From the earliest years, the GWR concentrated on passenger traffic and began to market excursions and holidays to the south-west. Ordinary people were discovering their country, encouraged by artists, such as the Newlyn School who painted Cornish Life from the 1880s and writers of popular fiction, such as Arthur Quiller-Couch of Fowey, Dorset’s Thomas Hardy, and Devon born Charles Kingsley who popularised tales of a romantic West Country, far from the hard lives of miners and fisher-folk.

Image: ‘Among the Missing’ Walter Langley 1884 – Penlee House Gallery & Museum

Kingsley’s 1855 bestseller inspired the 1860s development of the holiday village of ‘Westward Ho!’ on the North Devon coast but it was another entrepreneur, Christine Hamlyn, who was to be the moving force behind the sensitive development of one of what remains today as one of North Devon’s much loved romantic tourist gems – Clovelly.

Paddle Steamers and the Development of the North Devon Resorts

A new industry had been born which was to sustain the West Country into the 21st century – tourism. Clovelly on the north Devon coast is an outstanding example of its transformative effect. When Christine Hamlyn came to Clovelly in 1884, it was a down-at-heel fishing village. In the mid-1800s, Clovelly’s medieval harbour supported a fleet of 80 small herring boats, providing a livelihood for around 200 fishermen and their families crammed into tiny, dirty, cob and beach-pebble built cottages either side of a stream-filled cleft in the cliffs. The dynamic 28-year-old Mrs Hamlyn was determined to bring change, she progressively rebuilt the village adding dormers and floors to cottages in the latest ‘Arts and Crafts’ style. Charles Kingsley had written romantically of Clovelly as ‘a steep stair of houses.’ Christine Hamlyn seized on this publicity, she encouraged tourism, in the process turning around the fortunes of her villagers, she built the New Inn Hotel for her guests and encouraged the paddle steamer service which ran along the north Devon coasts to bring in the visitors to the village she loved.

It is still possible to experience the delights of the age of steam on a summer excursion on the River Dart on the last coal-fired paddle-wheeler, the restored ‘Kingswear Castle’.

Image: Kingswear Castle on the Dart – Photo – Bob Mark

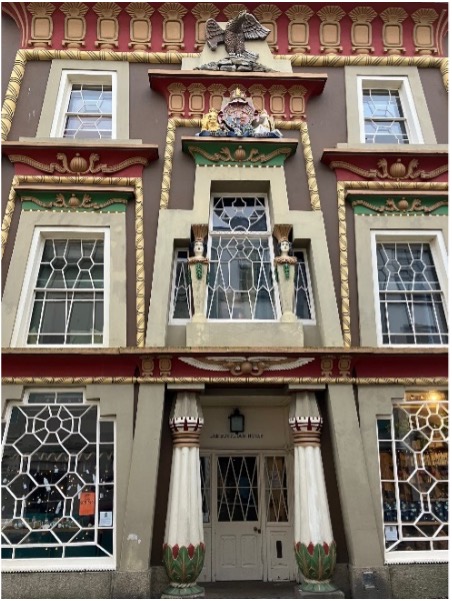

Other entrepreneurs spotted new opportunities from this tourist bonanza. John Lavin, a mineralogist, built the Egyptian House in Penzance. Mineral collectors visited his shop there to see and buy from his collection and wonder at his colourful Cornish recreation of ancient Egypt. Today the Egyptian House has been restored by the Landmark Trust and offers arguably the most unusual historic self-catering apartments in the SW.

All this hard-won prosperity was not to last. In 1914, on the outbreak of war, the GWR was taken under Government control and the coast – the pleasure ground for generations of trippers – was put to a new, defensive, use. Our story for next time.

Image: The Egyptian House, Penzance – Photo – Bob Mark

Written by Bob Mark

Chair, South West Coast Path Association

This article is the seventh in a series exploring the history around the landscape of the South West Coast Path. Read the other articles in the series:

History Around the SW Coast Path – Part I – Prehistory – The Age of Megaliths, Bronze and Iron

History around the SW Coast Path – Part II – Medieval

History Around the Coast Path – Part III – Late Medieval and Renaissance

History Around the Coast Path – Part IV – Civil War, Revolution and Invasion

History Around the Coast Path – Part VI – Elegance and Innovation in Georgian England

Discover a selection of Heritage Walks on our website and explore the past as you travel.