In Part IV of our history around the coast-path, we had reached the momentous events of 1688. A Dutch invasion and the deposition of the last Stuart King, James II of England. James II’s predecessors, Charles II, and Cromwell, had all fought the Protestant Dutch, in large part due to trade rivalries, fighting 3 wars against them. The popular accession of Dutch King William III and his English Queen Mary II as joint monarchs in 1688, overturned the previous 30 years of English Naval strategy. Now the most powerful country in Europe, Catholic France, under King Louis XIV, the ‘Sun-King’, became the enemy. What was worse, Louis pledged himself to help restore his fellow Catholic, the exiled James II, to the throne of England.

In 1689, James landed with French support in Ireland. A campaign that was to end in defeat in 1690 at the Battle of the Boyne at the hands of King William, despite James’ 6,000 professional French troop reinforcements. Although the Jacobite rebellion in Ireland had been defeated, the Irish campaign had exposed a grave problem. The English Fleet had no bases in the south west facing the Irish Sea and Channel Approaches. All the main English naval bases, Deptford, Sheerness, and Chatham, and the great naval anchorage of the Downs off Deal were in the South East. The nearest base to the south west was Portsmouth. Strategically of limited value to support an English Fleet charged with protecting still vulnerable Ireland, and the rich incoming Anglo-Dutch trade fleets taking advantage of the prevailing westerly winds to sail into the English Channel, past the gauntlet of French naval and privateer bases at La Rochelle, Nantes, Quiberon Bay, Brest, and St Malo. The English battlefleet from Portsmouth had to sail against the prevailing winds. Parliament was aghast that it took 2 months for the English Fleet to regain their protective station off southern Ireland after returning to Portsmouth for battle repairs in 1689.

Development of a Principle Naval Base in the South West and the Transformation of the Local Economy

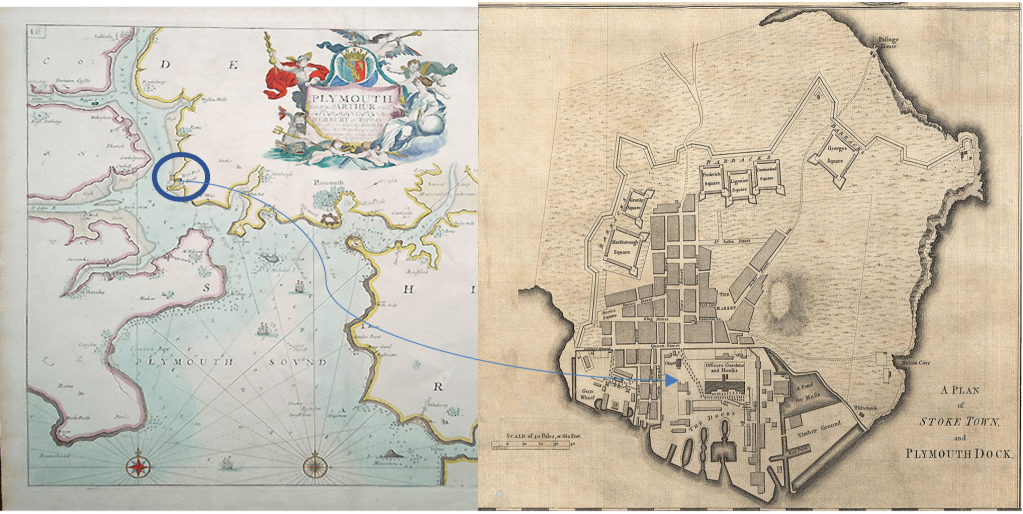

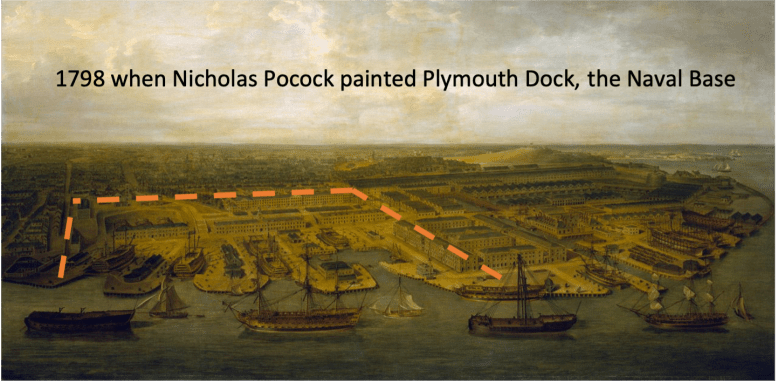

Something had to be done, and fast! In 1690, the Navy Board contract expert stonemasons from Portsmouth to oversee the construction of Plymouth Dock, (later renamed Devonport), on the Hamoaze on the River Tamar.

The ancient town of Plymouth with its port in the Cattewater and Sutton Harbour, overlooked by the massive citadel built by Charles II, was not chosen. In a far-sighted decision the Navy realised that the new naval yard would likely expand and require more space. By 1694 it was the most advanced naval repair yard. Plymouth Dock however had its problems, ‘the passage of the Hamoaze is very crooked, the current false by many eddies, the tides on springs rapid, the soundings foul, the shores dreadful, the coming in and going out too much commanded by the western winds’, so said Edmund Dummer, Assistant Surveyor of the Navy 1690. Even today the SWCP walker arriving at the ancient 11th century ferry-crossing of the River Tamar at Cremyll in Cornwall, to cross to ‘Admirals Hard’ in Devon, gets a glimpse of how difficult the entry to the Hamoaze is on a blustery day, and especially if lucky enough to watch a yacht navigating here under sail. So, before the mammoth undertaking of the 1.5 km long Plymouth Sound breakwater was completed in 1841, the Royal Navy Fleet in the south-west, had a problem, which was solved by establishing a Fleet anchorage in Torbay, sheltered from the prevailing westerly storm winds, but able to slip out easily as the weather moderated to blockade the chief French naval bases of Brest and La Rochelle.

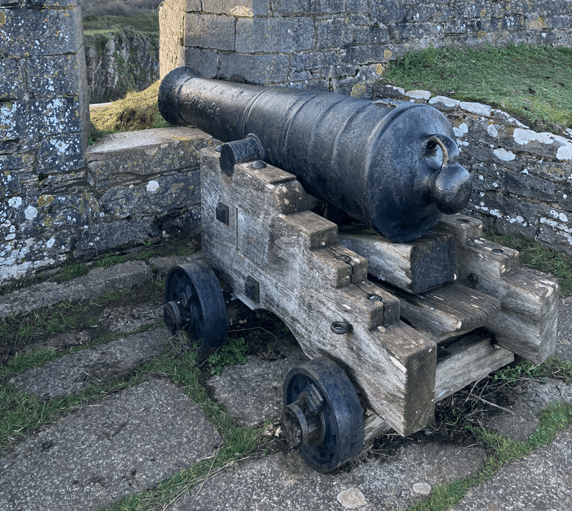

For the next 125 years, through 9 successive wars from 1688 to 1815, the strategy of the Royal Navy in this ‘Age of Fighting Sail’ was centred around a major repair yard, with stores, ordnance yards, fitting out basins and dry docks, in the military complex of Plymouth Dock and a Fleet Anchorage in Torbay, protected by the 3 forts and batteries established by the coast path at Berry Head, Torbay.

Photo: Berry Head Fort

The decision to concentrate the major Royal Navy fleet in the south-west had profound consequences for the local economy. By the 1750s the Western Squadron could very often have 14-15,000 seamen embarked, plus an equal or greater number of skilled craftsmen – shipwrights, sailmakers, blacksmiths, labourers, storemen, soldiers, and artillerymen working ashore. Far more than the population of any of the principal SW towns. This tremendous concentration of people needed feeding. Particularly as a 74-gun ship-of-the-line, crewed by between 500-650 men would typically carry 1,200 tonnes of provisions. The men would manhandle guns weighing up to 3 tonnes, manage 2 acres of canvas sails and maintain ~23 miles of rigging. Typical calorie consumption was twice our average, around 5,000 calories a day. Sailors needed to be well fed to carry out continuous blockading duties and west country farmers responded to the call by producing the food. Cattle were shod with iron shoes to allow them to be driven in herds of 3-400 from as far afield as Wales to the depot at Ivybridge and then driven on the hoof to Brixham. Fresh meat helps combat the dreaded sailor’s disease of scurvy, along with fruit and fresh vegetables. Before canning and refrigeration, sailing ships sailed with fresh provisions and live cattle for slaughter at sea to augment the less healthy salted provisions, salt pork and salt beef. Voyages and blockading duties could last months. However, navies are expensive, Parliament needed a means to foot the bill.

Taxes and Smuggling

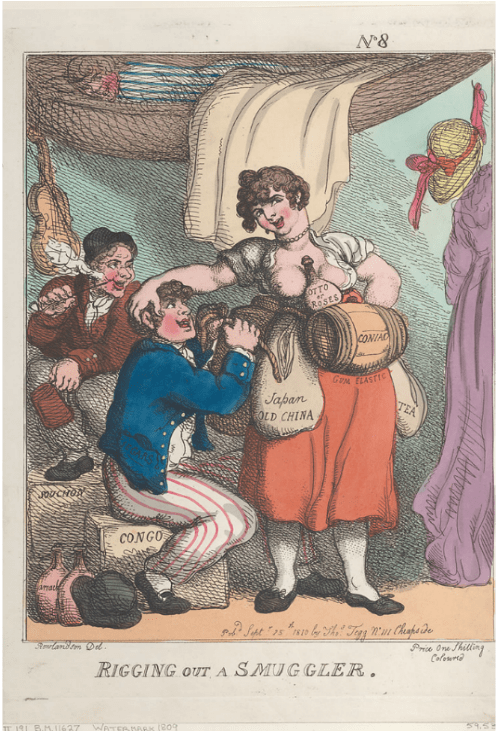

Between 1784 and 1792, Prime Minister William Pitt invested £64.5 million, about £50bn in today’s money on Defence. (By comparison the entire UK Defence budget in 2022 was £46Bn). At a time when the annual gross domestic product (GDP) was about £22 million in today’s money. These colossal sums were borrowed. Britain evolved the most sophisticated financial system in Europe. The Bank of England established in 1694, under William and Mary to fund the first of these French wars, allowed the Government to outspend a far richer French economy, because the national debt was guaranteed by Parliament which set taxes. The tax take had to rise to pay the interest and eventually pay down the national debt. Taxes were established on luxuries – especially tea, initially set in 1690 at 2 shillings a gallon on liquid tea brewed and sold in coffee-shops. By 1784 all tea imports were taxed at 120%. Taxes were also imposed on spirits, tobacco, and lace. Inevitably this led to a thriving smuggling trade. Rudyard Kipling caught the popular romance of the smuggling trade in his 19th century poem, but as Thomas Rowlandson’s 18th century engraving shows the ladies were far from innocent.

If you wake at midnight, and hear a horse’s feet,

Don’t go drawing back the curtain or looking in the street.

Them that ask no questions isn’t told a lie.

Watch the wall my darling, while the Gentlemen go by!

‘Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark –

Brandy for the Parson,

Baccy for the Clerk.

Laces for a lady, letters for a spy

And watch the wall my darling,

while the Gentlemen go by.

If you meet King George’s men, dressed in blue and red,

You be careful what you say and mindful what is said.

If they call you ‘pretty maid’ and chuck you ‘neath the chin,

Don’t you tell where no one is, nor yet where no one’s been!

The West Country ports were particularly well placed to carry on the smuggling trade because the Channel Islands were exempt from the English mainland tax regime and built up a thriving ‘free trade’ with France, building sophisticated relationships with the West Country smugglers. The tale of the ‘Smugglers Banker’, Zephaniah Job of Polperro (1750-1822), who went from poor schoolmaster to respectable entrepreneur who could afford to rebuild Polperro Harbour, much as we see it today, is interesting.

Here is an excerpt from one of his surviving letters from Jean Guile Junior & Company of Guernsey, 1778. ‘Mr John Baker recommended you to us and we make no doubt you will be punctual in executing every order we commit to your care. You are, we suppose acquainted with the commission for your trouble in receiving and remitting, [smuggled goods], which is half a percent besides all other charges, such as postage, and expenses in riding out, which last you will do with as much economy as possible.’ A Government Enquiry into smuggling in 1783, estimated the value of Guernsey ‘Free Trade’ with the Continent at £40,000 a year. Total Government income in 1783 was £12.7 million, 67% of which came from the customs. The delightful Polperro smuggling museum has more on Mr Job; and also, Robert Mark’s cutlass, a smuggler killed by Customs men!

The Preventive Service Water Guard, Riding Officers, Coast Guard, and the Origins of the SW Coast Path

It was imperative for the Government to stamp out the loss of revenues. The spread of the fore-and-aft sailing rig in the 17th century meant that contraband cargoes could be landed in any sheltered bay. In 1733, a Parliamentary Enquiry reported 2,000 smugglers prosecuted, 230 smuggling vessels seized, 250 customs and excise officers killed in the last 10 years. In 1780-83 it was estimated that 13 million gallons of spirits and 21 million pounds of tea were smuggled. In 1784, a Parliamentary Committee recommends the abolition of duties on smuggled goods, licensing of all fore-and-aft rigged vessels, no suspicious ‘hovering’ by vessels within 4 leagues of the coast and army patrols along the coast path to back up the hard-pressed Preventive Service Water Guard, the Customs and Excise ‘Riding officers’, who patrolled the coast in all weathers, and the Revenue Cutters, cruising offshore to intercept the smuggling sailing craft.

The Channel smugglers were encouraged by France. When Napoleon Bonaparte came to power he hit upon the idea of economic warfare – bleeding the British treasury dry of the national gold reserves. Three ports were allocated on the otherwise hostile French coast where the smugglers could only buy their contraband with gold. The French policy was hugely successful, British gold currency reserves declined by half in the three years from 1808. Massive resources were poured into the English anti-smuggling effort. A chain of coast guard stations is created, linked by a continuous coast-path regularly patrolled by ‘riding officers’, coast guard cottages are built overlooking practically every harbour and bay on the south coast. In 1787 Captain Swaffin of the Dartmouth based revenue cutter ‘ Spider’ seized the luggers ‘Hawke’ and ‘Nancy’ both were carrying spirits and tobacco. Unfortunately, they got off! The Dartmouth Collector (Senior Customs Official) raged …

‘ We think it almost impossible to convict an offender by a Devonshire jury, who are mostly composed of farmers, and generally the greatest part of them either smugglers or always ready to assist them in removing and secreting the goods.’

From the window of the Gara Rock lookout to the east you can see the revenue station on Prawle Point – still used by the National Coast Watch

The End of the French Wars and the Demise of the Smuggling Trade

In the 1790s Bigbury Bay was known to be one of the least well patrolled stretches of the South Devon Coast, it was a favourite spot for smugglers hiding in the 100 strong Brixham fishing fleet to sink cargoes of kegs for later recovery. In 1791, the Naval Cutter, ‘Nimble’,seized the ‘Persevering Peggy’ out of Brixham, she was not carrying contraband, but had sinking stones aboard as if to sink rafts of kegs and although fore-and-aft rigged had no licence. As the Revenue and Coast Guard tightened its grip, sinking of kegs off-shore became the standard method of concealment. It was economics that finally ended the great smuggling era, by the 1840s Britain adopted a free-trade policy that slashed import duties to realistic levels. Smuggling was no longer profitable.

By the end of the French Wars, in Georgian Britain the fruits of the industrial revolution and rising prosperity had created a new ‘Age of Elegance’. The coast was put to new, more genteel, use. Our story for next time.

Photo by: Sebastian Wasek

Written by Bob Mark

Chair, South West Coast Path Association

This article is the fifth in a series exploring the history around the landscape of the South West Coast Path. Read the other articles in the series:

History Around the SW Coast Path – Part I – Prehistory – The Age of Megaliths, Bronze and Iron

History around the SW Coast Path – Part II – Medieval

History Around the Coast Path – Part III – Late Medieval and Renaissance

History Around the Coast Path – Part IV – Civil War, Revolution and Invasion

Discover a selection of Heritage Walks on our website and explore the past as you travel.