Julian Gray, Director South West Coast Path Association

For many years there has been a perceived tension between trail managers and conservationists in protected areas. On the one hand, there is the view that habitats and cultural heritage need to be protected, and trails running through these areas and sites need to be managed to minimise the impact of people on natural and heritage assets. Others believe that the only way people will value and support future conservation and enhancement of habitats, species and culture is to connect people to these special places.

Often the situation on the ground is more nuanced, and we can find a balance between improving access and accessibility whilst still supporting efforts for nature growth and enhancement of the special qualities of the places visitors and locals love. Trails are a fantastic way to connect people with nature.

International Context

Globally, the view that trails can help to drive sustainability is becoming more prevalent. There are examples of how the power of a trail’s brand is being used to support regenerative tourism, nature restoration and health and wellbeing. The World Trails Network’s (WTN) Sustainability Task Team has been championing the concept of trail corridors as beacons of sustainable development and showcasing exemplar trails and projects, such as the Sendero Pacifico in Costa Rica. Internationally there are good examples of a transition from trail management to wider corridor conservation with the Appalachian Trail Conference changing its name to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and The Bruce Trail Association changing to Bruce Trail Conservancy.

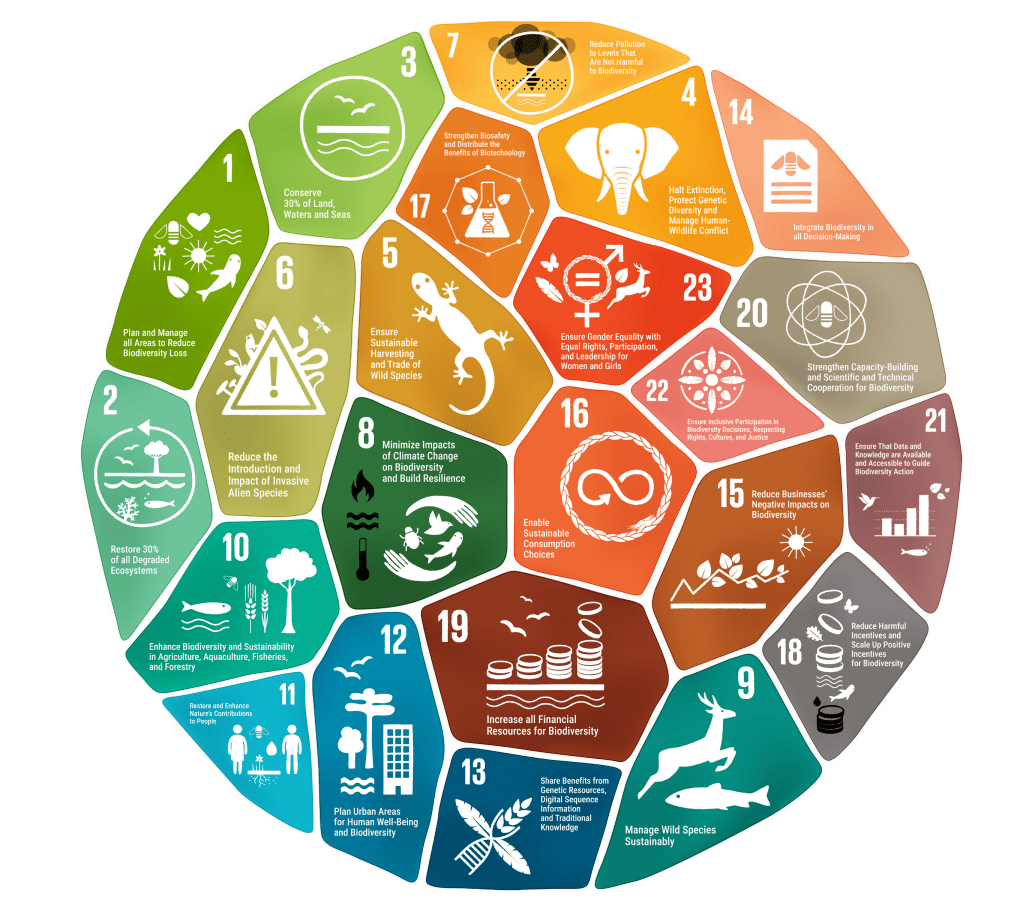

The WTN Conservation Task Team, working with the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) World Commission on Protected Areas, has successfully advocated for trail corridors to be classified as Protected Areas, helping to deliver global biodiversity targets. A resolution supporting this initiative has just been approved at the Abu Dhabi IUCN Conservation Congress. In the short-term this will help enhance recognition of the potential of trail corridors to support delivery of the international 30×30 commitment to protect and conserve a minimum of 30% of land and sea for biodiversity by 2030. In the longer-term it provides an opportunity to leverage trail brands for broader positive nature impact.

Coastal Margin and Coastal Wildbelt

The Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 created a once in a generation opportunity to improve access along the English coast through the designation of the Coastal Margin. This is the strip of land between the path and the sea, which includes beaches, cliffs, dunes, saltmarshes, and other coastal features. Under the new legislation walkers gain a right of access for recreation and enjoyment, unless there are restrictions for safety, conservation, or specific land management. These new coastal access rights add to the open access to mountain, moor, heath and down created by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000.

“One of the most ambitious ways we are opening up the natural world is through the England Coast Path”

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 25yr Environment Plan

The Coastal Wildbelt concept was conceived out of conversations at the end of 2018. Alex Raeder, South West Natural Environment Lead at the National Trust and myself were discussing opportunities to leverage the designation of the Coastal Margin for improving nature and connecting people with nature. The National Trust in the SW already had an ambitious coastal vision and it was clear the designation of the Coastal Margin would offer an opportunity to scale this up to the whole of the SW Coast and beyond.

Natural England was also interested in the opportunity to leverage the Coastal Margin for nature and there were discussions around a coastal protected area designation. In view of the time and resources needed for a new designation, and how divisive the process could be, it made sense to pursue a different approach based on international precedent, using a brand to drive change. In 2020 the Wildlife Trusts promoted the concept of a wildbelt to place nature at the heart of planning and protect land in recovery for nature from development. I took this name and created the concept of a Coastal Wildbelt and have been championing it ever since.

The Rumps, North Cornwall

Following the 2019 Glover Review a Protected Landscapes Partnership (PLP) was created to improve connectivity and joint working between the National Parks, National Landscapes and National Trails. In 2021 National Trails UK (NTUK) was registered as a new charity to give a stronger voice for the National Trails and formally represented the Trails at the PLP.

The Coastal Wildbelt concept began to gain traction and in 2023 it was embraced by National Parks England and NTUK as an opportunity for the PLP to deliver at scale and across a range of Protected Landscapes. With Defra support, the Coastal Wildbelt project found an institutional home at NTUK, whose role was to incubate the project. Two pilot interventions were identified, one in the North East with the North York Moors National Park and the other in the South West, involving the South West Coast Path Association. An early success has been recognition of the potential of the Coastal Wildbelt in Local Nature Recovery Strategies across Cornwall and Devon.

Extract from the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Nature Recovery Strategy

As the KCIII ECP is nearing completion the scale of the opportunity that the Coastal Wildbelt presents can be better articulated:

- The area of designated Coastal Margin will cover almost 950 square miles (245,000 ha) of England’s coastline

- Over 85% of this area, around 815 square miles, has the potential to deliver 1.6% of England’s 30×30 target for protecting land.

- 71% of the Coastal Margin is made up of Priority Habitats including mudflats, coastal and floodplain grazing marsh, coastal cliffs, sand dunes and saltmarsh.

- 81% of the area is designated for nature, mostly Sites of Special Scientific Interest.

The government’s 2025 update to the Environment Improvement Plan (EIP) recognises the potential of the Coastal Wildbelt in helping deliver its 30×30 commitment. The EIP also commits to extend the Access for All programme to include National Trails, supporting accessibility infrastructure in the countryside. These national level commitments to both the Coastal Wildbelt and National Trails are very positive.

The Coastal Wildbelt is now moving into a new phase. A steering committee was established earlier this year, and this will help transform the Coastal Wildbelt concept into a delivery programme, having real impact on the ground. I’m delighted to see how an initial concept has transformed into something that now has the potential to make a real difference.

Moving forward, a key priority is to understand the levers that are needed to unlock agri-environmental funding to deliver the Coastal Wildbelt nature ambition at scale. Other wider issues that need to be resolved, and which will create an enabling environment for the Coastal Wildbelt, include formalising the legal purpose of National Trails; creating a framework for National Trail Management Plans; and developing a mechanism for effective governance of the trail corridor. These are all changes that will improve the management of the National Trails and leverage these to better connect people to nature as part of our Natural Health Service. I look forward to championing this work, ensuring that the Coastal Wildbelt reaches its full potential.

Bossington Hill, Exmoor National Park, Somerset. Photo by Gary Holpin.

Author: Julian Gray, Director, South West Coast Path Association

Header image: Wildflowers in North Cornwall. Photo by Julian Gray.