Walking the South West Coast Path Through Italian Eyes

Why the South West Coast Path?

After completing the Camino de Santiago along the French Way (with its strong sense of community, constant human interactions, and endless conversations on the road) I felt the need for something different. I wasn’t looking for another pilgrimage experience, but rather for adventure, physical challenge, and raw nature. I wanted a trail that was less crowded, more solitary, physically demanding, and capable of testing my ability to handle autonomy.

The South West Coast Path (SWCP) seemed like the perfect answer. A path that never really gives you a break: constant climbs and descents, breathtaking cliffs, picturesque villages, and long, solitary stretches.

My goal wasn’t to walk the entire route, but to dedicate my three weeks of August 2025 to a long backpacking traverse carrying tent, sleeping bag, and sleeping pad. From 1 to 24 August, I walked from Minehead to Plymouth, covering 717 km with 25,000 metres of elevation gain.

PLEASE NOTE: This is Francesco’s story and he did not use the charity’s Official Guide to the South West Coast Path for reference, so there may be some variations in elevation and distances travelled. Route diversions and travel to accommodation will also impact daily distances walked.

Why an Italian trekker fell in love with the wildest trail in England

When you grow up hiking in the Alps and the northern Apennines, you think you know what “mountain effort” means: long climbs, rocky trails, altitude, sharp profiles. And when you’ve walked southern European routes like the Camino de Santiago, you’re used to a social atmosphere: villages every few kilometres, cafés, hostels, people everywhere.

The South West Coast Path was something else entirely. Something I didn’t expect. Something I had never experienced was a different way of walking, a different way of being on a trail.

Here are the things that surprised me the most as an Italian trekking the SWCP, and why this path has left such a deep mark on me.

In Italy and Spain, most long-distance trails pass through villages every few kilometres. Accommodation is frequent; cafés and small shops are part of the rhythm of the day. On the Camino, you almost never walk alone unless you choose to.

On the SWCP, I often walked hours without meeting anyone. The sensation was new and powerful. The silence, the space, the feeling of being a guest on the coastline rather than crossing through human landscapes, this changed the entire experience.

I wasn’t expecting such solitude in a country as populated and visited as England. But the SWCP, outside the main hubs, feels genuinely remote. For the first time in years, I felt completely responsible for myself: for my timing, my energy, my food, my safety.

In Italy, I’m used to trails where villages appear regularly, alpine huts are spaced at predictable intervals, and water fountains are everywhere.

Here, I learned a new discipline:

- checking the map each morning

- studying where the cafés or shops were open (if any)

- calculating how long I could go before finding water

- deciding before starting where I might end up camping

It wasn’t stressful, it was empowering.

The contrast with the landscapes I’m used to in Italy was striking:

- No high peaks, yet incredible elevation gain.

- Cliffs descending directly into the ocean.

- Valleys carved not by glaciers, but by wind, waves and rivers.

- Colours changing every hour with the light and weather.

- A coastline that feels alive—moving, breathing, shaping itself.

From outside the UK, you imagine England as a place of tidy landscapes, manicured paths, and frequent services. What I found was something much wilder:

- long sections without villages

- cliffs with a raw, untouched atmosphere

- very few infrastructures

- unpredictable weather

- a sense of isolation I rarely felt even in the Alps

The SWCP taught me that freedom and planning go hand in hand. If you want to walk it autonomously, you need to treat each day like a small expedition. It’s part of what makes this path special. I knew England had beautiful coastlines. I did not know they were this dramatic.

On most days, the landscape felt authentic and uncompromising, never altered to make the trail easier or more “touristic.” I loved that. It makes the SWCP feel real—just you, the trail, and the coastline.

In the Alps, the difficulty comes from altitude. On the SWCP, it comes from repetition: steep climb, steep descent, again and again, dozens of times a day. The body adapts; the mind needs to keep up.

There were stages where I asked myself: “Why am I doing this?” And there were sunsets that gave me the answer.

Walking here teaches patience, rhythm, and humility. It teaches you to accept that the coastline sets the rules; you just follow.

My trekking along the SWCP

Getting There: The Journey to the Start Line

(Before Day 1)

My SWCP began before I even put on my boots. On Thursday evening, as soon as I finished work, I rushed home: quick shower, quick dinner, grabbed the backpack I had prepared over the previous days, and my parents drove me to the airport. I had chosen a night flight to save time because my schedule was tight and I wanted to have the entire following day available to reach Minehead and start walking.

I landed in Manchester shortly after midnight. The airport was almost empty, and I managed to get a few hours of sleep on the chairs while waiting for the first train heading southwest. At dawn, I began the long rail journey to Taunton, in Somerset. It took hours, crossing the English countryside and small towns that already hinted at the landscapes ahead.

From Taunton I shared a taxi with two English guys I met at the station; they were also starting the SWCP. A lucky coincidence, as it spared us a long wait for the local buses. We arrived in Minehead, where a sculpture marks the official starting point of the path, in the early afternoon. Before walking a single step, I treated myself to a cream tea—scones, strawberry jam and clotted cream—as I had read about in The Salt Path. A symbolic way to open the journey.

First Impressions and a “Deceptive” Trail

(Days 1–2: Minehead – Porlock)

Stage 1 (13 km, 350 m ascent) from Minehead to Porlock winds along gentle green hills overlooking the Bristol Channel and the Welsh coast. It’s a peaceful landscape: woods, villages, sloping meadows, soft nature. I walked with the two guys I’d met earlier, and the day passed smoothly. In Porlock I found a panoramic campsite and a beautiful sunset.

Stage 2 (35 km, 1,414 m ascent) continued with the first real up-and-down sections toward Lynmouth. Entering Exmoor National Park, the path alternates woodland sections with open views, culminating in the spectacular Valley of the Rocks: one of the most beautiful landscapes of the whole route. I stopped for the night at a cliff-top campsite offering amazing views.

From these very first days, the SWCP reveals its true nature: a constantly undulating elevation profile, a relentless succession of climbs and descents that offer no real respite. Each section seems promisingly flat, but after every downhill comes another steep rise. This makes the trail “deceptive.” At first, the scenery (green hills, sea views, picturesque villages) may trick walkers into thinking that distance is the real challenge. The true difficulty lies in the unending, steep variations in elevation. It’s not the kilometres that weigh on your legs and morale, but the continuous effort of facing these climbs, which slowly wear you down and demand both determination and resilience.

Rain and the First Real Difficulties

(Days 3–4: Trentishoe – Woolacombe)

On Stage 3 (37 km, 1,615 m ascent), the weather changed dramatically. A storm hit just as I was climbing Great Hangman (318 m), the highest point on the SWCP. I reached Combe Martin soaked and freezing, forced to warm up in a café. I continued walking through rain all the way to Ilfracombe and then on to Woolacombe, where the sky finally cleared. It was a mentally tough day: the tourist campsites were crowded and not very welcoming to hikers with tents.

Stage 4 (42 km, 548 m ascent) should have been more relaxing: a long flat stretch following the estuary, mostly on the Tarka Trail cycle path. But persistent wind and rain made the walk tiring and monotonous. I reached Barnstaple, found a laundrette to dry my clothes, and had a classic fish and chips. It was my first real moment of combined physical and logistical difficulty: the SWCP gives nothing away—not even on the flats.

Entering Cornwall

(Days 5–7: Yelland – Hartland Quay – Bude)

Stage 5 (28 km, 489 m ascent) brought me to Westward Ho!, a tourist village without much charm. The day was sunnier, but the sense of solitude began to grow, closed campsites, few services, and long stretches through dunes and rolling hills.

Stage 6 (33 km, 1,409 m ascent), from Westward Ho! to Hartland Quay, marks the entrance into one of Devon’s wildest sections. I walked for hours without seeing anyone. I reached Clovelly without water, convinced I would find supplies in the village but the path stays high above it, so I had to push on until late afternoon.

Stage 7 (26 km, 1,451 m ascent) marked my entry into Cornwall. It was one of the hardest days: rain, strong wind, and a never-ending sequence of steep climbs. Luckily, I met another hiker with whom I shared the route to Bude; otherwise, the isolation would have been overwhelming. This was the first day when I genuinely wondered, “Why am I doing this to myself?”

Iconic Places and an Ankle Problem

(Days 8–12: Tintagel – Polzeath – Carnevas – Crantock)

Stage 8 (32 km, 1,560 m ascent) brought me to Tintagel via Rocky Valley: one of the most fascinating natural features of the entire trip. At Tintagel, the village famous for the castle tied to the legend of King Arthur I met Kasyhap, an English hiker finishing his John o’Groats to Land’s End journey. I would end up crossing paths with him and his family almost every day for a week.

Stage 9 (30 km, 1,464 m ascent) offered spectacular scenery. That evening, I stopped at Martin’s campsite. He hosted me, showed great kindness, and invited me to join a Methodist service. I appreciated the opportunity to experience something so different from my everyday life.

Stage 10 (25 km, 1,533 m ascent) was easy-going up to Rock, where I took the ferry to Padstow. After several tough days, having an easier stage was essential to recovery.

Stage 11 (29 km, 619 m ascent) alternated breathtaking views like the Bedruthan Steps with growing fatigue. I also saw the first remains of Cornwall’s mining settlements, silent witnesses of centuries of hard labor.

Stage 12 (29 km, 896 m ascent) began with meeting a friendly Italian couple at breakfast, then continued mostly in solitude. The trail crossed colourful cliffs and ruined mining buildings. The weather improved, but this was when I started feeling a painful ache in my ankle, which made every step harder.

Cornwall’s Symbolic Landmarks

(Days 13–19: St Ives – Botallack – Lamorna – Marazion – Mullion – Coverack)

Stage 13 (33 km, 688 m ascent) finally brought me to St Ives, after a seemingly endless bay of dunes and coves. Stage 14 (30 km, 1,152 m ascent) was one of the most technical: the trail toward Zennor is almost a scramble among boulders and cliffs. But the scenery is sublime, and reaching the sunset with the sun sinking into the ocean beside me was unforgettable.

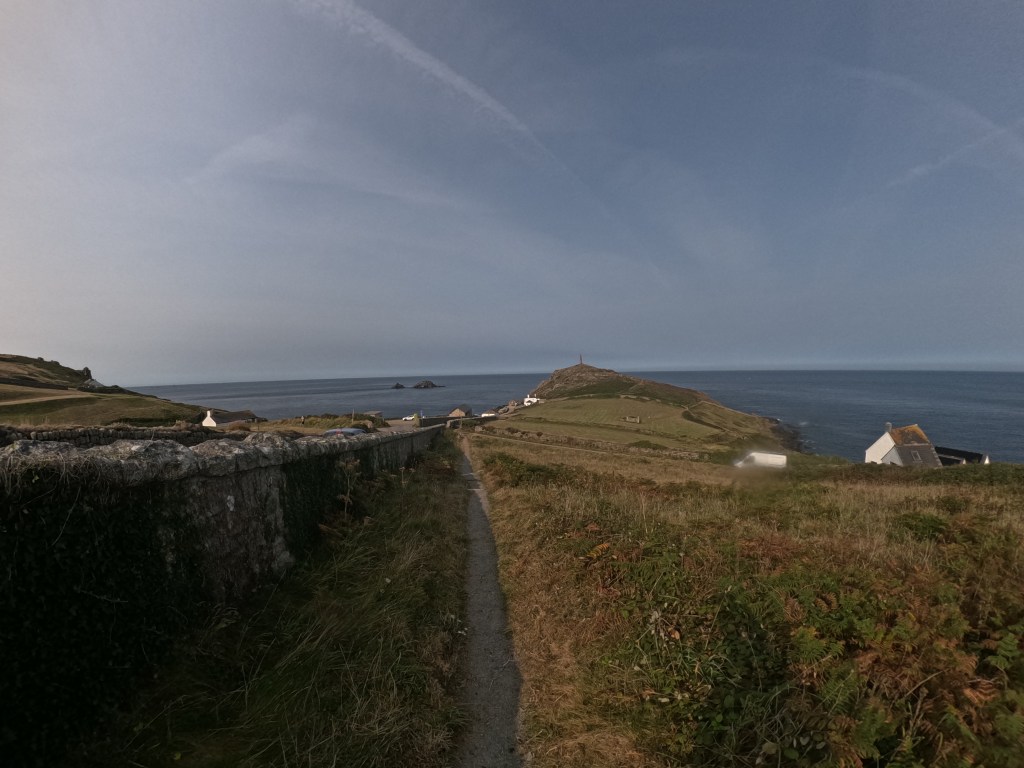

Stage 15 (33 km, 1,270 m ascent) crossed some iconic sites: Cape Cornwall and Land’s End, the westernmost point of England. Here I met Lilly, a trekker with whom I would share several upcoming sections. This was one of the most beautiful parts of the entire SWCP: tall cliffs, bays, seals and dolphins in the water below.

The next kilometers took me from Penzance and its botanical gardens to Marazion (Stage 16, 19 km), where St Michael’s Mount glowed at night under the lights.

Stage 17 (32 km, 1,390 m ascent) ended near Mullion, after passing the site where Guglielmo Marconi transmitted the first transatlantic radio signal.

Stage 18 (29 km, 1,660 m ascent) brought me to Lizard Point, the southernmost point of England, surrounded by dramatic cliffs.

Stage 19 (31 km, 922 m ascent) featured the halfway point monument and crossed the Helford Passage, less wild but still beautiful.

Picturesque Villages and a Changing Landscape

(Days 20–22: Maenporth – Portloe – Carlyon Bay – Polperro)

Stage 20 (34 km, 1,023 m ascent) led to Falmouth, taking two ferries to St Mawes and Place. Along the way I met Lilly again, and we walked together. I realized that Plymouth was finally close. Just a few hard stages left, followed by two easier ones. A sense of melancholy crept in: the journey was ending, but I was also grateful, because the hike had taken a toll on me.

Stage 21 (37 km, 1,501 m ascent) was demanding, with many steep climbs. Among the coastal villages I crossed, Mevagissey stood out, colourful houses overlooking a small harbour, fishermen at work, postcard-like scenery.

Stage 22 (29 km, 1,110 m ascent) ended in Polperro, perhaps the most picturesque village of the entire route, nestled in a steep-sided bay, full of charm and coastal character.

The Final Days: Reaching Plymouth

(Days 23–24: Whitsand Bay – Plymouth)

Stage 23 (28 km, 951 m ascent) was shared with Lilly along Whitsand Bay. The day ended with a sunset over the sea—one of those memories that stay with you.

Stage 24 (23 km, 619 m ascent) was the final one. I left at dawn after a cold night under a clear, starry sky. After passing Rame Head, with its stunning views of Plymouth Sound, I crossed the last hills, reached the ferry, and crossed into Plymouth. Leaving Cornwall behind, I officially entered South Devon. The route continued around the city’s fortifications and toward the historic harbour—marking the end of a journey full of encounters, dramatic scenery, and unforgettable moments.

What the SWCP Left Me With

The South West Coast Path isn’t for everyone. It’s hard, demanding, and often discouraging. But it is also incredibly rewarding.

Compared to Santiago—where community and pilgrimage create a shared sense of belonging—here solitude and nature dominate. You meet few trekkers, but those you meet become special. Each day is a test of endurance: against rain, wind, and fatigue.

The SWCP taught me adaptability, and how to find joy in small things: sunsets, cream tea, an unexpected pizza, a random encounter. It’s a trail I recommend to anyone seeking an authentic experience far from the usual routes, not a spiritual pilgrimage, but a full-on adventure, physically and mentally challenging, a deep immersion in wild nature and in the unpredictability of life.

I hope this perspective can help inspire more international walkers to discover and respect the South West Coast Path, as I did.

Why I would recommend the SWCP to other international walkers

Because it is different. Because it offers something few European trails offer at the same time:

- solitude without monotony

- wild landscapes without dangerous altitudes

- physical challenge without technical mountaineering

- a coastline that constantly surprises you

- an experience that feels authentic, not over-commercialized

For an Italian used to Alps, Apennines, and the Camino, the SWCP is a revelation. A journey into a different outdoor culture. A deeper connection with space, weather and the rhythm of nature.

Most of all, it is a rare opportunity to walk a long trail where nature is still the protagonist, and you, quietly, respectfully, are just passing through.

About the author

Francesco Botticini is an environmental engineer, GIS analyst, cycling guide and long-distance hiker based in Italy. Through his Scientific Trekking project, he combines slow travel, environmental analysis, mapping, and storytelling to explore landscapes in depth. After walking the Camino de Santiago and several Alpine routes, he completed the South West Coast Path from Minehead to Plymouth as a self-supported trek, documenting the journey through articles, photography, and interactive maps.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/botticinifrancesco/

Substack: https://substack.com/@scientifictrekkingproject

StoryMap: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories